Introduction

Conspiracy Code is an educational program designed as a course in American history, set up as a point-and-click adventure game. Players will explore near-futuristic Coverton City seeking out pieces of the history of the United States and using that information to undo the historical revisions caused by the elusive group known as Conspiracy Incorporated.

Below is a detailed analysis of this game roughly following Brian Winn's1 Design/Play/Experience framework, including:

Learning

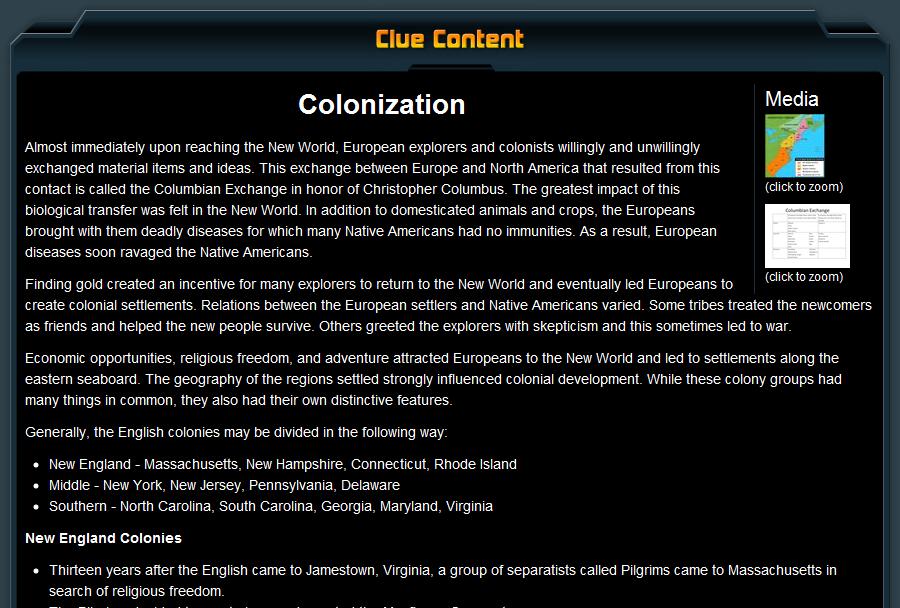

Conspiracy Code was built for the purpose of teaching American History at a high-school level. As the player explores the world, he or she will track down "clues" of Conspiracy Incorporated's historical tampering by receiving pages full of information about America's history. Players will often find an assessment in the corner of these pages that asks one question about the information presented on the page, which the player can refer to if he or she needs help answering the question. The game itself is designed much like a history course, splitting general themes of the course into weekly "missions", starting from the colonization of Plymouth and ending in modern times. Each mission is split up into several phases where players are expected to seek out a certain number of clues.

Once the player collects the last clue of that phase, that clue's page will remind the player to report what they have learned about history to the underground resistance that is trying to overthrow Conspiracy Incorporated. These prompts are used by the administrators of the Conspiracy Code program (teachers) to verify that their students are actually taking their lessons. In fact, there is a whole lesson plan attached to the game, with a culminating test after each mission and an exam after every five missions. The clues that students sniff out are gathered in the game and online in their personal accounts.

By playing Conspiracy Code, students are meant to learn:

- • The development of America as a nation from colonial times up until now

- • Information recall, which will help them pass tests

- • Note-taking, to help interrogate citizens who may or may not be working for the Conspiracy

- • Close reading, since that will identify important parts of the information

- • How to discriminate lies from the truth through the Interrogation portions

- • Evasion from suspecting eyes in order to gather clues

- • Problem solving: What can he use to get that clue?

Storytelling

In the near future, Coverton City has been struck by a terrorist organization known as "Conspiracy Incorporated". This group seeks to alter what has been recorded in American history in such a way that the general public would not notice the alterations. Through these tactics, Conspiracy Incorporated aims to conquer the world. However, there are people who know about this group's intentions, and they seek to stop these plans from being carried out.

Classic rock fan Eddie Flash and Techie Libby Whitetree are two new agents who seek to expose and overthrow Conspiracy Incorporated. Guided by the Bio-Electronic Navigator (BEN), Eddie and Libby are led to a conspiracy theorist who leads an Underground resistance that wants a piece of the shadowy organization. Eddie and Libby's job is to collect information about the history that Conspiracy Inc. seeks to alter and report it to the resistance. The first stop on this dangerous assignment is a local museum suffering from malfunctioning historical exhibits. Here, they will search out America's colonial history and expose agents of Conspiracy Inc, who inexplicably disappear when revealed.

The story does a great job of engaging the player, seeing as this is aimed at teenagers. Despite the gravity of the situation presented, the game is kept rather light-hearted most of the time. Eddie and Libby have some enjoyable back-and-forth banter between them, and some of the prominent side characters also feature some decent humor. Seeing Eddie distracting guards and other museum patrons with his keytar has yet to get old, too.

The story does have a few confusing elements to it, however. The big issue is that Eddie and Libby are trying not to look to suspicious when they sneak around and collect clues. However, the suspicions from NPCs do not start at all unless our two agents try to hack a camera or scope out the area, even if they are inside a room meant for restoring exhibits that looks like it is meant for museum personnel only. Why wouldn't their mere presence in an important room like this set off alarms? Then again, this could be considered nitpicking.

Gameplay

The bulk of Conspiracy Code's gameplay involves the player navigating the area and collecting clues about the history Conspiracy Inc. is trying to rewrite. As the player explores, he can switch control between Eddie and Libby. Both of them can search for information, collect clues, talk to NPCs, and hack into cameras. However, they each possess individual abilities, as well. Eddie can use his keytar to distract human NPCs, and he can let out a sonic signal that can pinpoint the location of the next clue (if he is close enough to it). Libby's powers are based on other gadgets, including a clue-pointing radar, a chameleon-like suit, and an electromagnetic pulse. By using these powers, the player can sneak by obstacles to get to his destination. If he tries to check for clues when security is not detained, however, the kid the player is controlling becomes more suspicious to everyone else. The NPCs also become more suspicious whenever Eddie or Libby uses one of their powers or hacks a camera. If the NPCs suspicions climb too high, alarms go off, and the player could be arrested. Luckily, if the player just leaves things alone for a little while, suspicions die down to a safe level.

While the exploration and clue-finding parts work, the stealth aspect of gameplay involved here tends to detract from the primary learning goal of Conspiracy Code: teaching students about American history. The challenge for this portion of the game does not have players wondering when they will learn about Custer's Last Stand; instead the challenge here becomes a question of how to circumvent the cameras and guard to snag the clue in the datapad on the shelf. This part of the game is fun for trying to get the MacGuffin, but what does it have to do with American history?

The learning goals of the game are better achieved by other portions, however. Once the player has collected enough historical clues, he can use his wristwatch to hypnotize citizens into stating what the citizens perceive as historical fact. Normal citizens will be able to recite accurate historical information. Conspiracy agents, however, have been brainwashed into believing that the rewritten history is the truth, so they will spout lies when interrogated. If the player recognizes that the "citizen's" info doesn't mesh with history, the player can mark that person as an agent and then challenge him. At this point, the player must fill the blank in the historical sentence with the right word or phrase. Do that enough times, and the agent will be defeated and disappear (to Eddie's confusion).

This part of the gameplay does a better job of reinforcing the primary learning goal than the exploration. It asks the players to recall information that they have picked up, and it tests to see if the players can distinguish lies from the truth. The clues they collect are also available for them either in the game or on their account, if they ever need to refer to it.

User Experience

Controls for Conspiracy Code are pretty basic. The player moves with the WASD keys and examines things with the mouse. The player can right-click on many objects to bring up a menu of options for that object, such as talking to an NPC, hacking a camera, or checking for clues. If the player moves his mouse too far away from the menu, however, that menu disappears until he right-clicks again. In the bottom left corner, the player has a HUD that he can use to switch between characters, use that character's powers, check his suspicion levels, and open menus. This much of the HUD is fairly transparent and doesn't really interfere with the player's experiences in-game.

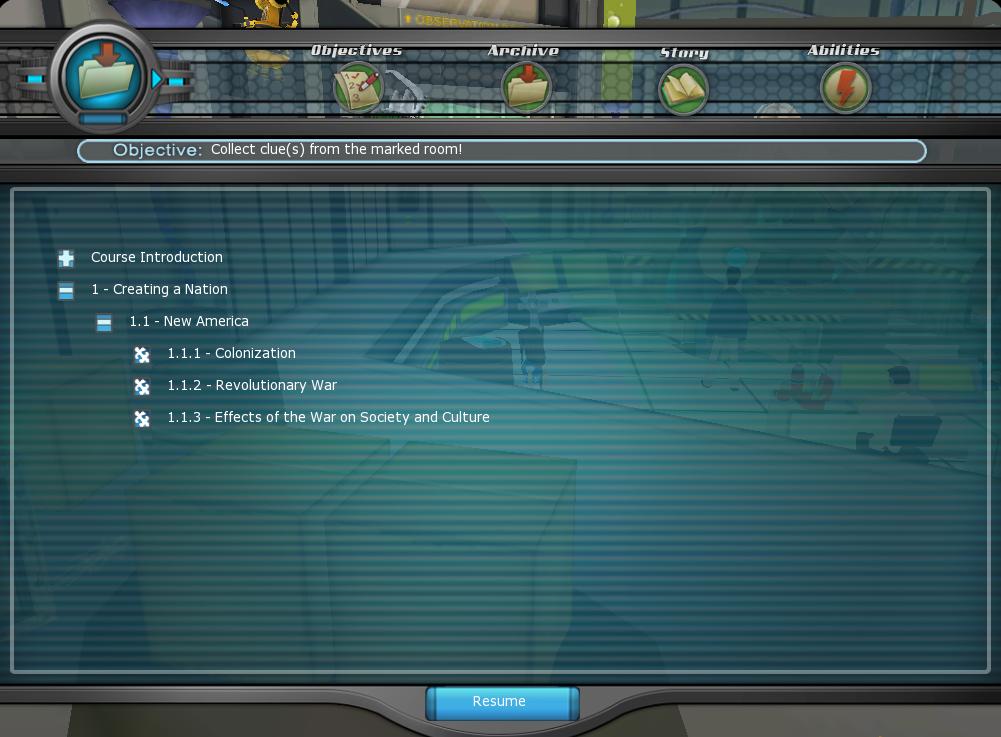

Your pause menus are all rather intuitive and straightforward. The map screen shows the whole area you are exploring, the room you are in flashes with white borders, and your destination room flashes with red. Your acquired clues are organized into an outline that you can expand by clicking on the main topics, and you can read them by clicking on the clue itself. These kinds of menus are helpful resources that the player can access any time, and they only mean to pause gameplay at the player's command so that he can check this menu.

Technology

When one creates a point-and-click adventure, it is wise to create a space that your target audience will actually want to explore. The low-fidelity cartoony art style of the game works very well for Conspiracy Code. Paired with the humorous dialogue and characters, it helps create a colorful, fun-looking world that is appealing to teenagers and seems inviting, despite the danger afoot.

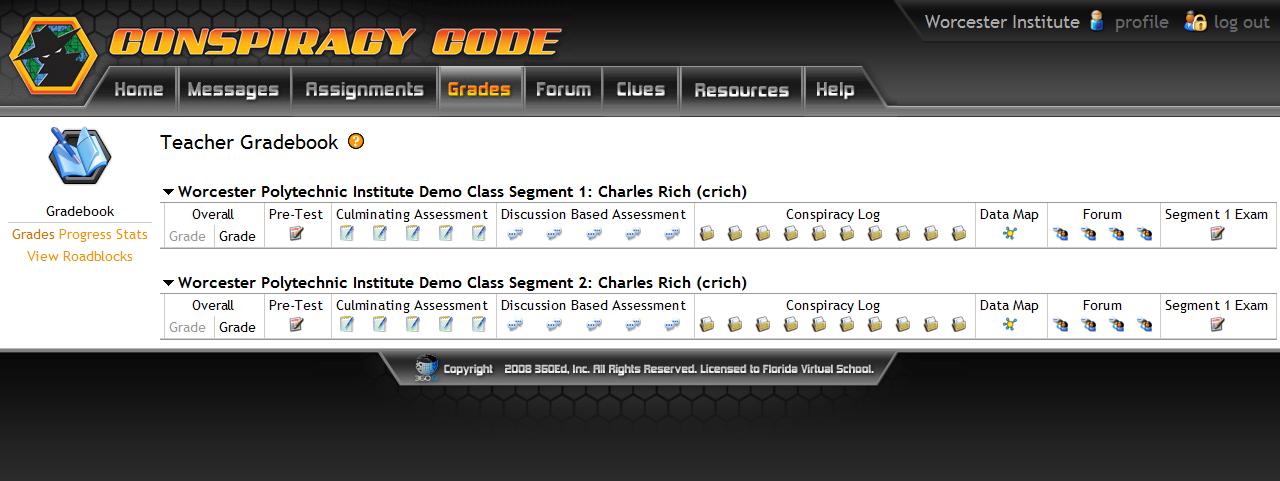

Possibly the most interesting technology used for the game is the networking aspects. As mentioned before, this game is meant to help high-school students learn about American history, so much so that the game itself becomes the course. To that extent, both students and teachers sign up for accounts. Throughout the course, students will receive prompts and assignments to submit to the Underground, as well as the citizens of Coverton City, to inform them of the information they have recovered. (Really, they are submitting to those who will grade them.) This allows the teachers to check the progress of their students and guide them in the right direction should they be off-course. The game also possesses measures to discourage cheating, as the students are held in high integrity in order to succeed at the game.

Assessment

The game was developed in cooperation with the Florida Virtual School (FLVS), an acclaimed pioneer in providing Internet-based education to students from kindergarten to Grade 12. They have already integrated Conspiracy Code into their curriculum.

In October of 2009, Governor Charlie Crist awarded 360Ed the Governor's Business Diversification Award in Entrepreneurship for its work on Conspiracy Code and another game called Burn Center. They also received the Metro Orlando Development Commission's 2009 William C. Schwartz Industry Innovation Award. Governor Crist commented that 360Ed received his award for its "demonstrated ingenuity, civic leadership, and significant contribution to diversifying and strengthening Florida's economy."2

Conspiracy Code itself also won awards in late May of 2010. The game has earned the Florida Virtual School two CODIEs for Best Reading / English Instructional Solution and Best Social Studies Instruction. It has also earned a Gold Award for Learning Impact from the IMS Global Learning Consortium.3

Conclusion

All in all, the game is a good piece of work meant to teach kids about American History. While the stealth segments might distract from the learning for a little while, the game does reward students with lessons on how our country came to be. It engages the students very well with fun gameplay, a vibrant world, and fun characters. Be warned, though: this game is not something that can be downloaded and played easily. This game was designed as a course to be taught in schools, so the solo experience does leave a player feeling hollow and irritated. This player most likely would have enjoyed the game more if he had some more people to play with – if he had played this game the way it was meant to be experienced.

References

- Winn, Brian. The Design, Play and Experience Framework. In R. Ferdig (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Effective Electronic Gaming in Education. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2009, pp. 388-401.

- Sand, Erik. "360Ed Wins State and Local Awards for Entrepreneurship and Innovation." For Immediate Release 2 Oct 2009: p. 1, 360Ed. http://www.360ed.com/site_media/uchi/pdf/360Ed%20Gov%20&%20EDC%20Awards%20release.pdf. 7 Feb 2011.

- Sand, Erik. "Florida Virtual School Wins Multiple Awards for Game-Based Courses." 360Ed News Contact 27 May 2010: p. 1, Florida Virtual School. http://www.360ed.com/site_media/uchi/pdf/CODiE%20Awards%208-1-10.pdf. 7 Feb 2011.