Introduction

At-Risk is an interactive training simulation that teaches faculty and staff at educational institutions the common indicators of psychological distress and how to approach students that exhibit these indicators. The player engages in conversations with emotionally responsive students to practice and learn techniques for reflective listening and interviewing.

Below is a detailed analysis of this game roughly following Brian Winn's1 Design/Play/Experience framework, including:

Learning

The purpose of the At-Risk program is to teach teachers how to identify and approach students that may be going through psychological distress. In the classroom, the player reads each troubled student’s profile to learn what he can about the student. If he feels like the student is somebody to talk to, the player will want to talk with the student.

When the player begins his conversation with the first student, he is given guidelines about what he needs to do in the following case. His job is to gather information about the student, decide whether you need to make a referral to the counseling center, and convince the student to visit the center if he decides that the student should see a counselor. The player should not try to force counseling on the student, however, nor should he be trying to diagnose the student’s problems himself. The player is being trained merely as an advisor, NOT as a professional psychologist. His focus should not be on trying to fix the student himself but on talking the student into seeing somebody who can help.

Players of the At-Risk simulation should be able to:

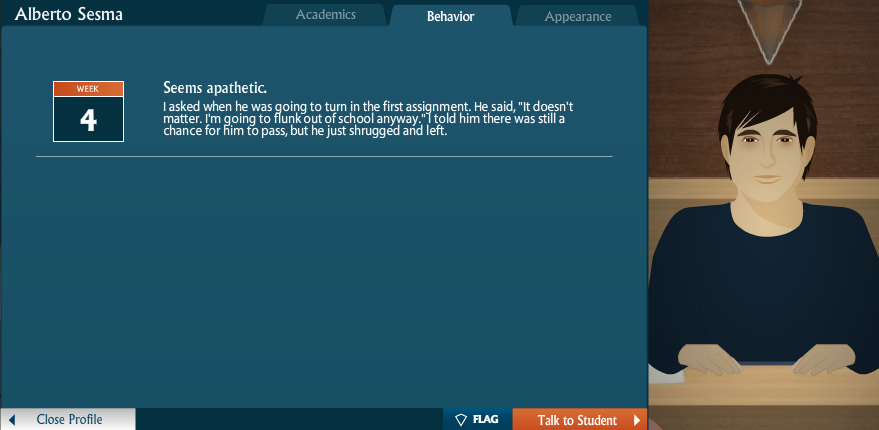

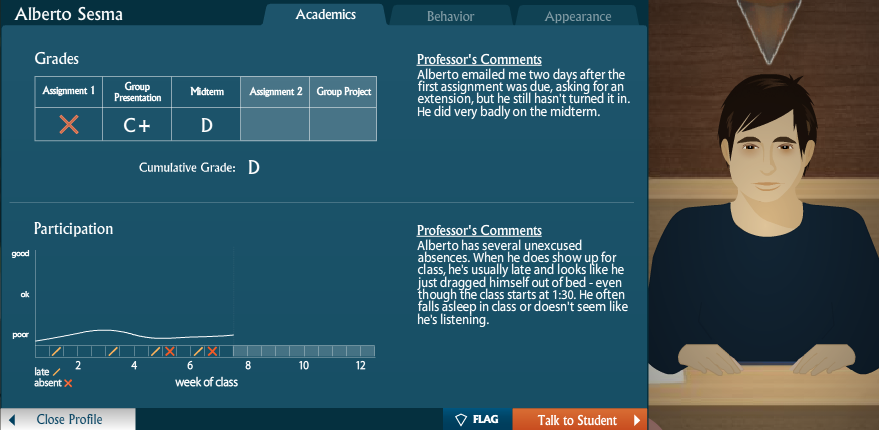

• Closely observe information about students (i.e. attendance in class, unusual notes about appearance, odd quotes like “I’m just going to flunk out anyway”)

• Decide whether or not they should talk to a particular student based on their unusual behaviors. Falling asleep in class is worrisome, but is that enough to decide whether the student is at risk?

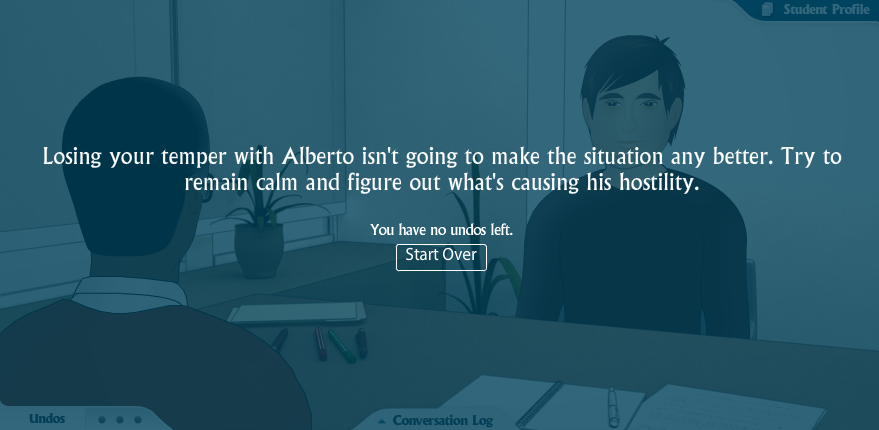

• Remain calm, even in the face of adversity. An aggressive student does not have to be matched with an aggressive response.

• Talk to the student if in doubt. It never hurts to talk to the student, even if the conversation doesn’t lead to the counseling center.

• Decided whether or not the student in question ought to seek help. If the lack of sleep is caused by playing games all night, is that a reason to seek help?

• Convince a student who may be in mental pain to attend counseling.

• Make the student feel comfortable while talking to them. Asking how the student is doing may help him open up to you.

• Avoid diagnosing the student themselves. Even if it sounds like depression, the player is NOT a trained psychologist, is not learning to be one, and thus has no right to malpractice.

• Avoid telling students to simply get over their problems. Telling a negative person to think positively does not yield any new information and may agitate the student or make him or her feel uncomfortable.

• Address any mentions of suicide. Is Alberto merely joking about killing himself, or has he seriously thought about it? This is definitely something to bring up to the counseling center.

Storytelling

The demo version provided by Kognito features Dr. Bill Hampton, a college professor teaching a Business Marketing class. This semester, he has been observing the progress and behaviors of his students very carefully. He has taken special notice, however, of five of these students: Alberto, Gwen, Doug, Jared, and Fiona. Each of them exhibits behavior that Dr. Hampton finds troubling or unusual. Because of this, he wants to talk to the students to see if they are at-risk of falling into mental distress.

When Dr. Hampton finally confronts Alberto to his office, the student begins acting antagonistic. For example, if the professor mentions that Alberto is falling asleep in class, Alberto snaps back that other students do it, too. Dr. Hampton’s responses during the conversation will turn the tides one way or the other. Telling Alberto that he needs to think positively or rethink his attitude will yield little more than an annoyed “Yes, sir.” By remaining calm and collected and responding that way, Alberto may begin to open up to his teacher a little more.

This kind of story is mostly beneficial for the learning purposes. Dr. Hampton has noticed odd behaviors that some of his students are exhibiting. Since the game is trying to instruct teachers on paying attention to these oddities, it is good for the in-game teacher to have taken note of these facts already. The conversations invoked by the students turn out to be realistic but engaging, as long as Dr. Hampton doesn’t yell at them to shape up or ship out.

It is hard to tell, however, whether the player is supposed to be Dr. Hampton. He speaks to the player to teach him what to do before the conversation starts, instead of being written so that he is learning these skills along with the player. Dr. Hampton seems to know what needs to be done up until the conversation begins, and at that point, the player assumes the role of this professor. Sympathizing with Dr. Hampton would be easier if the player simply assumed his role while receiving instruction and advice from an assistant.

Gameplay

Gameplay begins at a broad overview of the classroom, where the player is able to look up the troubling students’ profiles. Using these profiles to examine the student and his or her behaviors, the player will decide who he thinks is in need of a meeting with Dr. Hampton.

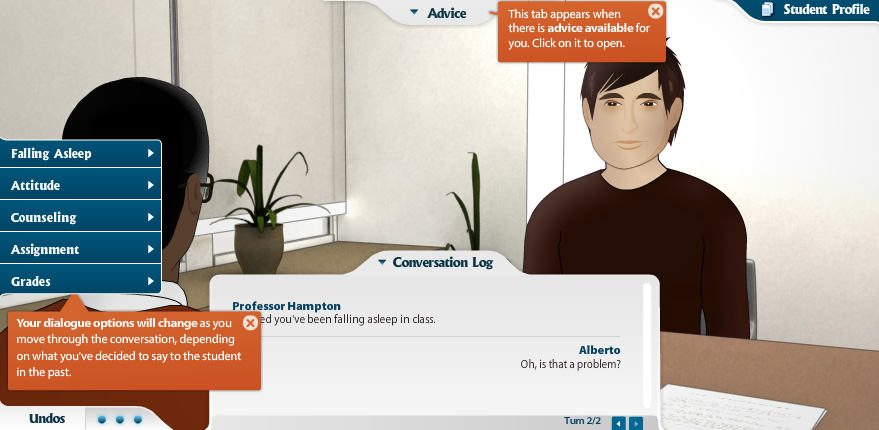

Once the student has arrived to see the teacher, the player will select topics for Dr. Hampton to talk to his student about. Through these topics, the player will converse with the student, and the student will respond depending on what the player chooses to say, with more branches to the conversation tree becoming available when the player advances the conversation. This communication between player and student is used to gather information about the student’s attitudes and to discern the proper course of action to take with the student. If the player feels the student is in anguish, the player will make his goal to convince the student to visit the counseling center to seek professional help.

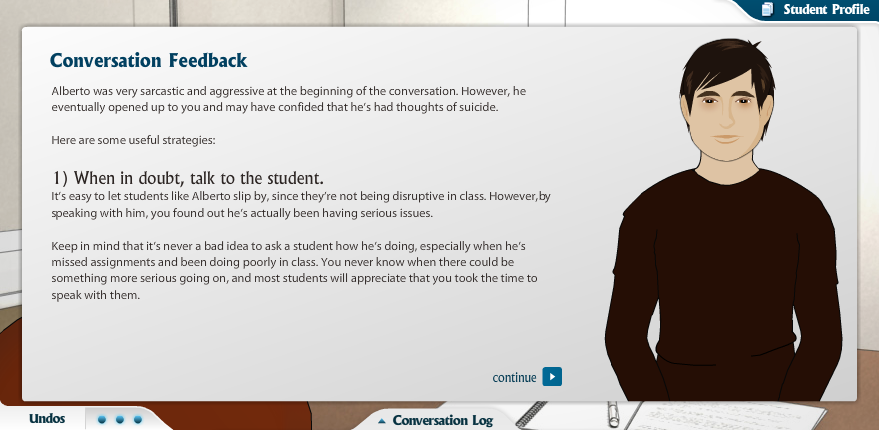

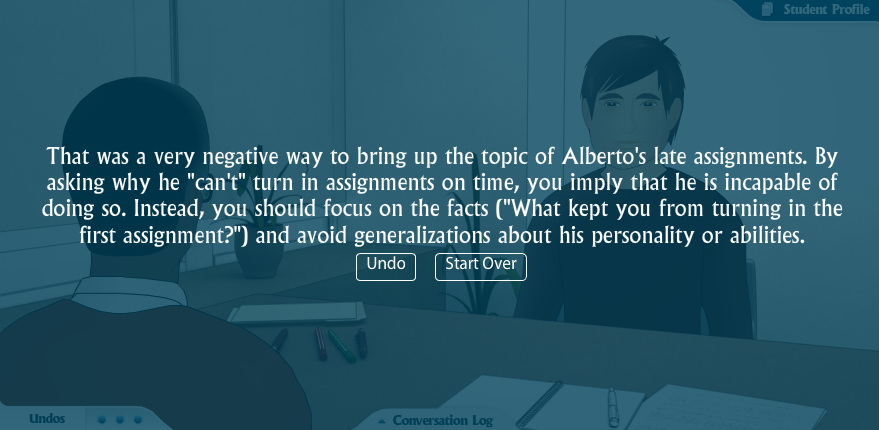

The player must be wary of trying to push the student too hard, however. Quoting after-school special clichés like “think positive” or trying to diagnose the student yourself will make the student feel uncomfortable or aggravated. When this happens, the player will be advised to not repeat the mistake he just made, and the progress of the latest conversation block will be undone. The game will only allow the player to undo his mistakes three times, however, before he must start the entire simulation over. To avoid having this happen, the player should be able to talk with his student calmly and without judgment.

This gameplay does well at achieving the learning. It puts a heavy emphasis on gentle persuasion and penalizes forceful ordering or diagnosis. Remember, the player is not being trained to be a professional psychologist. All he is doing is trying to give a recommendation for students to seek counseling if they need it. In this regard, the game is fairly balanced. Even if the student acts hostile or in opposition, as long as the player does not try to force anything on his student, the conversation will still proceed normally.

User Experience

The user interface for At-Risk is intuitive. The player has both visual and

audio feedback. The primary modes of

interaction deal with reviewing a student's details and choosing the

next thing for Professor Hampton to say. The former is organized by

a tabbed report that displays grades, participation, comments, behavior

and visible changes of the student. Here are two examples:

The player can also view specific changes in the student's appearance

in order to determine whether or not the student might be at risk:

The latter (the professor's conversation) is controlled with dialogue

trees. When the player chooses the next thing for the professor to say, the conversation is played

back with audio. Much of the experience is created by listening to the conversation

and the tone, pace and inflection of the speech. Without sound, this simulation

would be far less immersive.

The player also has a conversation log, an advice box

and popup tips. All of these elements either shrink, disappear or compress

their content in some way so as to not obstruct the view of the conversation

participants. They help the player along and are easily understandable on the

first play. Here's an example of all these elements:

Overall, the interface was relatively transparent. I did not experience a learning curve

or any hindrance because of the user interface. It was also pretty obvious when you did

something wrong:

Technology

The game is implemented in Adobe Flash and deployed over the web. This was an especially

good decision because the game is architecture, operating system and browser independent.

Furthermore, the web as a platform allows a very broad audience to easily access the game.

A typical scene:

As you can see, the art style is kind of cartoony. While it's not the latest and greatest

bleeding-edge graphics, the experience has lost nothing to a lower fidelity technology. The

intent of the game developers did not require a high visual realism to be successful. However,

it was absolutely realistic enough so that the player would not be distracted by something that

looks fake.

The technology chosen to drive the applications was also not highly sophisticated. Much of the

experience is delivered through sound and text--the visual representation merely associates a

setting and characters with some imagery. There's not really any apparent advanced artificial

intelligence behing the conversations to create rich and genuine respones. However, the responses

do vary and the dialogue trees can exclude some branches. Generally speaking, the depth of the

dialogue is not so much that scripting them would be unmanageable.

Assessment

As a result of a study across 40 states that included 327 high school teachers, using a control

group, the following feedback data was collected:

Additionally, a study of 1,450 university and college faculty at 72 universities and colleges

found the software to be helpful:

And even students felt encouraged to engage other students that they perceive to

be experiencing psychological distress, as a result of studying 512 students at

35 universities and colleges:

It would appear that At-Risk is immensely successful at encouraging people to acknowledge and

engage psychological distress. Furthermore, the studies also found that people are more aware,

more confident in their ability to help, more likely to approach students and better at identifying,

approaching and referring students after playing At-Risk.

Images courtesy of Kognito Interactive.

Conclusion

Overall, At-Risk is a well-made simulation that manages to teach its players to actually talk to others about their possible problems without seeming cheesy for a second. In fact, it frowns upon that cheesiness, as well as straightforward commands to "get over it", in favor of allowing the players to learn more about the students they talk to. It does suffer a bit from being unclear whether Professor Hampton is supposed to be the player or a coach. Another character, either an assistant to Hampton or a less experienced teacher that Hampton is teaching, would hook this disconnect back together. Other than that, the game does bring a realistic feel to how one can deal with students in mental distress despite its cartoony artwork through its conversation.